The Lost Carving, David Esterly, St James’s Church Piccadilly, London

August 20, 2023

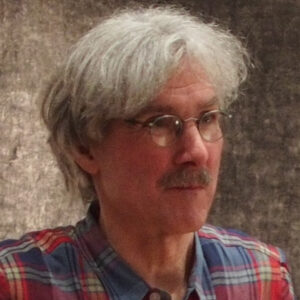

It was London in the 1970’s and unaware that his life was about to change its course completely, David Esterly, an American Fulbright scholar who had just completed a PhD from Cambridge University, was out walking with his fiancée, Marietta von Bernuth. As they passed St James’s Church at Piccadilly Marietta suggested they duck in to see the Grinling Gibbons. Esterly had never heard of Grinling Gibbons but followed her into the church and down the aisle to the altar, behind which was ‘a shadowy tangle of vegetation, carved to airy thinness.’ The delicate cascades of flowers, fruit and foliage before him took his breath away.

My steps slowed, and stopped. I stared. The sickness came over me. It seemed one of the wonders of the world. The traffic noise on Piccadilly went silent, and I was at the still centre of the universe.

He later told The New York Times in 1998 that he had been overawed by the power of the carving to render such natural beauty.

It seemed to me beyond belief that a human hand had fashioned those seashell swags, drooping bellflower chains, birds with laurel twigs in their beaks and dense whorls of acanthus. My fate was sealed.

Grinling Gibbons

Esterly had just encountered the work of a seventeenth century genius, known as the ‘Michelangelo of woodcarving’. Grinling Gibbons was Britain’s unofficial woodcarver laureate, a man whose name belongs with other luminaries of British craft heritage, such as Thomas Chippendale and William Morris.

Gibbons was born of British parents in Holland, where he lived and was educated. In 1670, at the age of nineteen, he went to London in response to an invitation from King Charles II for Dutch carvers and artists to work in Britain. London was in the process of being rebuilt in the wake of The Great Fire of 1666 and there were plenty of opportunities for a young carver.

Gibbons’s Renaissance training in drawing and woodcarving in Northern Europe had focused on the realistic expression of nature; almost single-handedly he had taken this to a new level, producing carving of unsurpassable perfection. As the collector and man of letters Horace Walpole observed in 1763: ‘There is no instance of a man before Gibbons who gave to wood the loose and airy lightness of flowers’. Compared to the dull and static swags and drops of conventional carvers’ flowers, those carved by Gibbons were transformed into fluent blossoms that Esterly describes as possessing ‘the juice of life’.

Grinling Gibbons had three advantages over English carvers: his education in drawing; his chisels, finer than any seen in England, and his choice of limewood from the linden tree as a carving medium. Compared to English oak, lime is a softer, lighter wood; firm and crisp, it is more easily manipulated to create the delicate details of nature. Its blond colour, without the grain of oak, lends greater emphasis to the form, which Gibbons often dramatised by setting it against darker wood.

Gibbons’s first important commission was to decorate an apartment at Windsor Castle, a huge project that required him to work with other artisans. The English master carvers William Emmett and Jonathan Maine were so impressed that they swiftly adopted his realistic style. The combination of flowers, fruits and foliage appealed to the British, a nation of gardeners, and throughout the late seventeenth century this naturalistic style dominated interiors, sprouting, as Esterly describes it, ‘like kudzu through the palaces and churches and houses of the realm.’

Apprentice to a Phantom

Esterly’s response to this encounter with the Gibbons carving at St James’s prompted him to attempt what university had trained him to do: write a scholarly book about the man. He set about this with zeal but realised that in order to reach a thorough understanding of how Gibbons had developed his style, he would need to know more about carving.

Holding a chisel and carving into wood for the first time was revelatory. Esterly loved its physicality, the way it forced him to his feet, his whole body moving with the blade as it dug experimental valleys into the wood. He experienced the dynamic tension at the heart of woodworking; the rear hand on the chisel provides propulsion and power, while the front hand on the blade resists that propulsion. Hands pitted against one another give the carver command over the blade: the greater the tension, the greater the control. It was this first use of the chisel, not the previous epiphany in the church that became the turning point of his life. ‘The genie was out of the bottle never to return.’

Reflecting later on how these life changing events unfolded he wrote:

Fate is in the before and after. Before the bolt strikes, something charges the atmosphere, some long foreground of decisions and actions. And the sudden flash doesn’t always light up a clear path forward. But if you read the portents right and set your trajectory accordingly, fate and desire seem to come together, life swerves, and what happens after looks like what was always meant to happen.

Esterly turned his back on academia. He had studied Yeats and the philosopher Plotinus and was to discover that their ideas continued to inform and enrich his new life as a woodcarver. Marietta took a part-time job as a cook at a country house on the south coast of England and they were offered an eighteenth century cottage on the estate. Esterly spent the next eight years there, teaching himself this ‘primal manipulation of the world’ and labouring to recover the long dead tradition of Gibbons’s style of carving.

Carvers are bringers of shadows, stainers of the white radiance of eternity, wreckers of a smooth plank. They live in a world permeated by error. Every carving starts the same way. You stare at a drawing on a board and think to yourself, I may not know exactly what should be there but at least I can see some things that shouldn’t. So you start by rounding the corners of a sawn-out peach, thinking, Well, I can’t go wrong with that anyway.

Esterly had a spectacular talent. He strived to emulate rather than reproduce the works of the great man. Discarding the lace, ribbons and cherubs that were the conventions of the day, he introduced an asymmetry into his compositions that he felt Gibbons would have loathed. Nonetheless, by working in the style Gibbons had invented, Esterly had inevitably drawn close to a man whose sublime skills filled him with trepidation.

During these years he felt the ghost of Gibbons was almost taunting him. In an interview with CBS he said: ‘He was always coming into my workshop late at night and saying, ‘You know, it looks the way I do it, but I do it better than you do,’ sort of whispering over my shoulder.’ Fifteen years after taking up carving, and despite the opinions of others that his skills had equalled or even surpassed those of Gibbons, Esterly heeded the words of the ‘ghost’ and he reached a dead end.

A malaise had come over my professional life. I was weary of being an epiphyte on Gibbons. I felt petrified by that looming presence, turned to stone. Blocked. Blocked as a writer is blocked, blocked as anyone is whose confidence in what they are doing has failed and who cannot see a path forward.

Where could he go from here? Should he ignore, imitate, rob or channel his guru? Gibbons had literally become a monkey on his back and Esterly was plagued by bad dreams. In one there was a chilling vision of old pale carvings high on a wall in a great room, that were engulfed by flames while he looked on, filled with dread and guilt – for in this dream he knew it was he who had set these Gibbons carvings alight.

Hampton Court Palace

By terrible coincidence, a few days after this dream Esterly heard on the radio news of a devastating fire at the British royal palace of Hampton Court. The damage had occurred in an addition to the building that had been designed by Christopher Wren. Esterly was familiar with this part of Hampton Court because it contained Gibbons masterpieces from his final period. He had intently studied photographs of the sixteen sets of carvings in four rooms and a beautiful frieze in the King’s bedroom. Appalled that the culmination Gibbons’s lifework might have been lost, Esterly felt as if a close friend had died. He composed an obituary for these works which he sent off to a British newspaper.

Shortly after the piece was published Esterly received a call from the government architect telling him that, although the carvings were charred in places, most of the damage had come from smoke and water rather than flames. Protected by their high position on the walls beneath deep cornices, they were thought to be restorable. There was one exception: a beautiful over-door drop, a long pendant of flowers and leaves in the King’s bedroom, had been reduced to ashes. The architect was determined to have that lost carving replaced.

After Esterly put the phone down, it occurred to him that he, a man who had always loathed ‘slavish imitation’ was possibly the only woodcarver with the skills to tackle this job. And a new thought stirred: he began to wonder whether, in reproducing this carving, he might break the spell that Gibbons seemed to have cast over him.

Gibbons had been the air I’d breathed for years, and I’d thought that, if anything, being too close to the man was the source of my problems. But could it be that I wasn’t close enough? A heretical idea was stirring. Perhaps what was blocking me wasn’t knowing too much about the man, but knowing too little.

Esterly had found distasteful the rules of the old guild days that demanded blind obedience from craftsmen to their master. Yet the ghost of Gibbons seemed to be telling him: ‘Follow me, if you want to find the truth.’ And when he thought about the challenges of reproducing a Gibbons carving, he realised that although he had made regular pilgrimages to see his work, all over England, he had never actually picked up a piece, or properly examined it from the back or the sides. Esterly made a ‘Faustian pact’ to devote one year of his life to reproducing the lost work, uncertain about what he might receive in return. Knowledge? Liberation? He was unsure.

In Esterly’s book The Lost Carving: A Journey to the Heart of Making (2012) he revisits his notebooks, accounting for this most challenging year of his life when fifteen years at his workbench ‘melted into nothing’ in the face of the master from the grave at Hampton Court Palace. ‘I saw that I’d understood as a child, thought as a child, carved as a child.’

The Times Literary Supplement review described the book as a meditation on ‘imitation and illusion, technique and genius, and on the strange physical and mental immersion that enables the transmission of vision from brain to hand, tool to wood.’

Esterly did achieve the knowledge and liberation he sought. It was only by reproducing Gibbons’s work and coming as close as he could to identifying with the man that he could subsequently free himself from him. He came to realise that the activity of carving was something bigger than both of them:

Gibbons wasn’t the giant whose shoulder I was riding on. The giant was the act of carving, the profession itself: the making of a carving, the making of anything. Making itself. The Ancient of Days in all of us, the impulse to create.

Endings

After completing the work at Hampton Court, Esterly moved with Marietta to America where they converted a barn in the rural hamlet of Barneveld in upstate New York. Although he had lain his ghost to rest, three portraits of Gibbons at different stages of his life hung on the walls of his workshop. Amongst the nut-scented limewood shavings, Esterly would select the tool he needed from the serried rows of old chisels and gouges on his workbench, and set to work. He had collected over one hundred and thirty of these tools over his lifetime. Some were were hundreds of years old, with the names of the original owners carved into their handles. The first chisel he ever used, the one that had turned his life around, he continued to use every day.

His work was slow and painstaking and he created only about fifty pieces in his lifetime. There are letter-rack carvings, witty and masterful assemblages of objects contained within the grid of a rack, that constitute a portrait of their imagined owners, such as Thomas Jefferson and Doctor Compton; fantastically surreal botanical heads, and exquisite carvings for overmantels.

Esterly was a modest man who said he was ‘profoundly uninterested’ in himself; he had taken ‘refuge’ in his work, and it was there that he could be found. At the age of seventy-five he died in June 2019, from Motor Neurone disease (also known as Lou Gehrig’s), the cruel affliction of the nervous system that causes progressive and catastrophic loss of muscle control. Interviewed in his final year, he said:

You know, nobody should feel sorry for me. I’m pretty old, have led a very interesting life. And you gotta die sometime. I’ve lived my life by the connection between brain and hand. And now, I’m ending it by precisely that connection being snatched away from me. So, to me, there’s something richly meaningful about that.

Music

The Fairy-Queen by Henry Purcell, Bremer Baroque Orchestra

Music was often featured in the work of Grinling Gibbons. In one of his late carvings for Charles Seymour, the Duke of Somerset, at Petworth House, he carved a group of violins and an open manuscript of Henry Purcell’s opera The Fairy Queen which had only recently debuted on the London stage in 1692. It is most likely that Gibbons saw this first performance.

The Fairy Queen is a hybrid between a play and an opera. It is based on William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream but modernised to suit Restoration tastes and simplified to accommodate the musical entertainments, or masques that were inserted, often at the end of each scene.

Its original production in 1692 was lavish and one spectator wrote:

This in Ornaments was Superior…especially in the Cloaths, for all the Singers and Dancers, Scenes, Machines and Decorations, all most profusely set off, and excellently perform’d, chiefly the Instrument and Vocal part Compos’d by the said Mr. Purcel, and the Dances by Mr. Priest. The Court and Town were wonderfully satisfy’d with it; but the Expences in setting it out being so great, the Company got very little by it.

Henry Purcell, the great English composer of Baroque music, died just three years after composing The Fairy Queen at the age of thirty-five. After his death the score was lost and was only recovered early in the twentieth century.

Connection

In 1757 William Blake was baptised in Gibbons’s font and lived most of his life nearby. In 1918 the writer Robert Graves married his first wife here, watched from the congregation by the great First World War poet Wilfred Owen. Soon after the wedding Owen returned to the front in France and was killed, just one week before the Armistice.

Notes

A year before I left Sydney for England, my boss gave me The Lost Carving as a gift. Her choice was typically discerning and timely: Esterly’s story of reinvention, and his discussion about the process of creating, was serendipitous for me. For the last ten years the role of caring had increasingly tipped into my life and work and I was feeling an imbalance. Like Esterly, I had an urge to make things, an impulse to create. At various stages of my life art-making has grounded me, and restored me to myself. I love its process and where it leads me and I particularly identify with this description of Esterly’s:

The workroom begins to fade away. On go the hands. The mind slips its mooring and lets the river take it where it will.

On my very first day in London I walked along Piccadilly and nosed around a market in a courtyard off the road. A free recital was in progress and I went in, barely registering that I was walking into a church. And there it was, the Grinling Gibbons altarpiece. This extraordinary work is so fine that it feels as if one of those graceful stems or fragile blossoms might quiver in a breeze. Its beauty filled me with joy and the wonder of having come across it so unexpectedly.

I returned to St James’s whenever possible on my visits to London. Its modest and beautifully proportioned interior are the perfect foil for Gibbons’s Baroque ornamentation. He also carved the baptismal font and the organ case on the western wall. But the undeniable focus of the building, its very soul, is that altarpiece, which was recently restored to its limewood blondness.

Each time I visited, St James’s was buzzing and welcoming. Aside from the lunchtime recitals and handicraft market, there was a food market in the courtyard on Mondays and Tuesdays (it seems to have been replaced by ‘Gin & Jazz’ over summer). On another occasion an Easter celebration for a local school was in full swing. Behind the church is a shady garden retreat planted with evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs, a quiet place for reflection.

See below for the link to its website to see the St James’s very busy calendar of events.

Weblinks

The documentary: The Glorious Grinling Gibbons – Carved with Love.

A film about Gibbons’s work at St James’s Piccadilly.

This article ‘Grinling Gibbons – Carving a place in history’ provides a good overview of his life and work.

A clip of a CBS interview with David Esterly, filmed towards the end of his life.

David Esterly’s website.

The website for St James’s Piccadilly.

Woodworking is listed by Heritage Crafts UK as a viable craft, meaning there are sufficient craftspeople to transmit the skills to the next generation. Other crafts are not faring so well. Here is a list of crafts from Heritage Crafts UK that are endangered, critically endangered and extinct in Britain.

Sources

Ducas, June. ‘The Carver to the Crown was a Sculptor’, The New York Times, October 25, 1998

Esterly, David. The Lost Carving: A Journey to the Heart of Making, Viking, 2012

Grinling Gibbons – The Michelangelo of Woodcarving, a film about the legendary woodcarver and his work at St James’s Piccadilly. Produced by St James’s Church Piccadilly in Association with the Grinling Gibbons Society, April 15, 2021

Seelye, Katharine Q. ‘David Esterly, 75, Master Carver Steeped in History and Nature, Dies’, The New York Times, June 21, 2019

Tagholm, Roger. Walking Literary London: 25 Original Walks Through London’s Literary Heritage, New Holland, 2001

‘The delicate craft of wood carver David Esterly‘, interviewer: Faith Sale for ‘Sunday Morning’, CBS NEWS, June 2, 2019

Another really interesting article.

The link to endangered crafts article was most helpful. When will folks wake up?

Thanks, Marilyn. Yes, that list of endangered and extinct crafts was sad. I did discover though that David Esterly inspired quite a few others to follow in his footsteps, so that style of detailed woodcarving is flourishing. Hope all’s well with you.