Finding the Words and the Bards

June 12, 2023

Language is something that most of us take for granted. Yet when a language dies, many secrets of a culture die with it. Its wisdom, spirit and plant lore, its orally told history and stories, all can disappear within a few generations. Also lost is a distinctive way of being. Cornish (Kernewek), one of the oldest languages of Britain, has been saved from such a fate – but only just.

Cornish is descended from the Brythonic group of Celtic languages along with Welsh and Breton. It was one of two closely related language groups brought to Britain by the Celts. The invasion of Romans and later Anglo-Saxons pushed large numbers of Brythonic speaking Celts westwards to Brittany, Cornwall and Wales. With geographic separation, the languages diverged and grew independently of one another.

In the middle ages Cornish was at its peak and spoken by roughly 38,000 people. Its decline began as English became the more convenient language for trading in fish and tin with strangers from beyond Cornwall’s borders. It didn’t help that the gentry tended to look down on Cornish speakers, regarding them as quaint and inferior. But the death knell for Cornish as a common community language came in the early sixteenth century with Henry VIII’s break from the Catholic church. The Tudors subsequently imposed the use of English in Cornish churches, where services had been conducted in Latin. It was also decreed that the Cornish people should use the Book of Common Prayer, which was written in English. A point blank refusal was shot back to King Edward VI:

We the Cornish men (wherof certen of us understande no Englysh) utterly refuse thys newe English.

This intransigence incited the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549. A thousand Cornishmen, mostly fishermen, farmers and miners, were slaughtered in a bloody battle with the King’s Army in Devon. Hundreds more were captured and executed. Sir Anthony Kingston led the King’s army into Cornwall to hunt down and kill the surviving rebels. Reaching Bodmin, he asked for the gallows to be prepared and dined with the mayor, a rebel sympathiser. After the dinner Sir Anthony hanged his host. In all, more than ten percent of the population were killed.

The Tudors also stopped the plays. During the Middle Ages there had been a thriving dramatic tradition. Mystery plays based on stories from the Bible, and miracle plays about the lives of the saints were written and performed in the Cornish language across the county. But because of their links with Catholicism these plays were banned.

By 1602 the British translator and aristocrat Richard Carew observed that the number of monoglot Cornish speakers was small and increasingly confined to western parts beyond Truro. He recorded a number of colourful insults such as molla tuenda laaz, which he translated as ‘ten thousand mischiefs in thy guts’. It seemed the Cornish people didn’t take to him; although many could speak only English, when he asked them a question their response was usually: Meea navidna cowza sawzneck, which Carew took to mean: ‘I cannot speak English’. In fact it meant ‘I will not speak English’.

Watching their language dying before their eyes, a small band of Cornishmen set about recording it. For the last forty years of the seventeenth century and the first thirty of the eighteenth, they translated existing Cornish texts, collected songs, and compiled word-lists, epitaphs, verses, proverbs and other scraps in the spirit of the motto:

Cuntelleugh an vrewyon us gesys, na va kelps travyth – Gather the fragments that are left, that nothing be lost.

A fishwife from Mousehole called Dolly Pentreath was thought to have been the last fluent native speaker of Cornish. After her death in 1777, although the Cornish people still retained some knowledge of their language, it was no longer considered to be a live, community language.

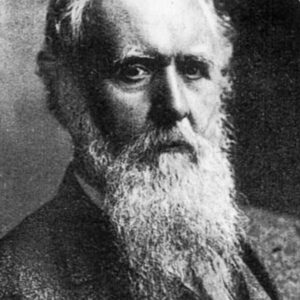

Henry Jenner

Reviving Cornish as a ‘living language’ became the life work of Cornishman Henry Jenner. As a boy he had been intrigued to learn from his father that there had once been a Cornish language. ‘Then I’m Cornish – that’s mine!’ he said and the spark stayed with him into adulthood. With the help of other scholars he painstakingly constructed a ‘unified Cornish’ based on records left by historians, fragments surviving from medieval plays, and interviews with the elderly in Cornwall’s western reaches who retained remnants of the language.

Jenner observed that Cornish is embedded in a strong sense of place:

The spoken language may be dead, but its ghost still haunts its old dwelling, the speech of West Cornish folk is full of it, and no one can talk about the country and its inhabitants in any sort of topographical detail without using a wealth of Cornish words.

For visitors to Cornwall, an everyday reminder of its otherness can be found in its place names. Many contain prefixes describing the characteristics of that place, as explained in a rhyme recorded by Richard Carew in his Survey of Cornwall (1602): ‘By Tre, Pol and Pen shall ye know Cornishmen’.

Tre – Homestead – Trelissick, Tregony, Trebah

Pol – Pool – Polperro, Polzeath, Polruan, Polkerris

Penn – End/Headland – Penzance, Pendeen, Pentewan

These names, along with hundreds of others, provided vital information for Jenner and other revivalists in their attempt to reassemble the vocabulary and structure of Cornish. In 1904 Jenner published his influential A Handbook of the Cornish Language.

Restoring the Bardic Tradition

In recognition of his efforts at a Cornish Celtic revival, Jenner was made a Bard of the Breton and Welsh Gorsedhs, the Bardic assemblies of Cornwall’s linguistic cousins. And in 1928 he helped to re-establish the Cornish Gorsedh, reviving a Bardic tradition that had died out in Cornwall in the eleventh century.

Since ancient times, Bards have been celebrated and revered. The Greek writer Strabo (63 BC – AD 24), in his Geographica, counted the Bards as one of three groups of men ‘held in exceptional honour’ among the Gallic peoples. The Bards were the poets and musicians, the holders of the history and genealogies, weaving tales that venerated or ridiculed their rulers.

Of the three gathering places for Bards in Britain, one was at the Bronze Age stone circle of Boscawen Un in Cornwall, where the first modern Cornish Gorsedh was held in 1928. Jenner based the ceremony on the Welsh version which dates back to the 1700s. One of the twelve Bards invested at this first ceremony was the writer Arthur Quiller-Couch, a great friend and mentor of Daphne du Maurier and Kenneth Grahame. He took the Bardic name: Marghak Cough (Red Knight).

Gorsedh Kernow

The Gorsedh Kernow celebrates an ancient storytelling tradition that links Cornwall with Wales, Brittany and the Isle of Man. Its function is to maintain the national Celtic spirit of Cornwall. As an organisation it encourages the study of Cornish history, literature, art, music, dance, sport and language. A major part of its annual Bardic assembly is the awarding of Bardships to those who have shared their learning about the Cornish culture.

While the Gorsedh makes it clear it is not affiliated to any religious, Druid or pagan practices, the ceremony is imbued with ritual and Bardic trappings. Strabo referred to the Gauls’ fondness for ornament: for chains, bracelets and golden collars, and the dyed garments worn by dignitaries, details that today’s Cornish Bards have taken to heart. The ceremony casts its eye back to the time of the ancient Cornish kings and the legendary immortality of King Arthur is woven into the ceremony with the inclusion of the song, ‘He shall come again’.

As pictured, during the ceremony there is a swearing of fealty to Cornwall as a Celtic Nation, on a sword symbolising that used by King Arthur. Each Bard places their right hand on the shoulder of the Bard in front, to give them symbolic contact with the sword, while the Grand Bard speaks:

An als hwath Arthur a with,

Yn korf Palores yn few:

Y Wlas hwath Arthur a biw,

Myghtern a veu hag a vydh.

Still Arthur watches our shore,

alive in the body of the Chough: [a Cornish bird]

His kingdom still Arthur owns,

A king he has been and will be.

The Gorsedh Kernow ceremony is held in a different location each year. In September 2019 it took place in the far western coastal town of St Just, an important mining area close to the settlement of Pendeen which was featured in this story.

In 2010 UNESCO changed the status of Cornish from ‘extinct’ to ‘critically endangered’ and identified it as being in the process of revitalisation. There are only a few hundred fluent speakers of Cornish and the battle to save it is not over. But the steps first taken by Henry Jenner in the 1920s are bearing fruit.

The language is not just the preserve of scholarly people from traditional organisations. It is taught in a number of schools (five thousand primary school students recently took part in a ‘Go Cornish’ programme). An increasing number of Cornish speaking films are being produced and it is featured in leading British film director Mark Jenkins’s latest folk horror Enys Men (2022). Indie singer Gwenno recently released two albums of songs written entirely in Cornish including Le Kov (2018) about the Cornish struggle of Kernewek (the Cornish language) and the culture’s clash with tourism. In this video Gwenno speaks about how she adopted a playful approach to Kernewek, rejecting ‘the idea that you need to treat the language as a fragile object to be kept in a glass case.’

At a time when languages are dying out faster than ever before, these signs of revival are heartening, for in the words of writer Tim Winton: ‘There is nothing more intimate, or more powerful, or restorative than language.’

Music

Hayl Dh’agan Mammvro – Hail to the Homeland, sung by Buccas Four

This Cornish anthem is featured each year at the Kernow Gorsedh ceremony. It is sung after the initiate Bards have received their Bardic names and been welcomed into the College of Bards.

Hail to the homeland! – great bastion of the free.

Hear now thy children proclaim their love for thee;

Ageless the splendour – undimmed that Celtic flame,

Proudly our souls reflect the glory of thy name.

Sense now the beauty – the peace of Bodmin Moor,

Ride with the breaker towards the Sennen shore;

Let firm hands fondle the boulders of Trencrom – Sing with all the fervour then the great Trelawny song.

Hail

Notes

I came across this Gorsedh in a wonderfully synchronous way. Hearing from a friend a little about the Bards and their special annual event, I took note of it as a subject to research and photograph. Two weeks later I had set out from Penzance to photograph the abandoned Botallack mine that perches dramatically on a cliff edge by the sea. But, as is so often the case in Cornwall, the day that began with sunshine turned dismal, so I returned to the nearby village of St Just, having noticed earlier that preparations were underway for some kind of celebration. When I arrived I was astonished to discover it was the Bards who were assembling on the town’s outskirts for the start of the Gorsedh.

The mood was upbeat and friendly. Onlookers had staked out their spots along the procession route; dogs wore the Cornish yellow tartan or Cornish flags. The Bards chatted amongst themselves as gusts of wind played havoc with their head-gear. With a roll of drums, they set off, led by a band and flag bearers from Cornish Communities and the Celtic Nations. More than one hundred Bards walked two by two through the streets of St Just towards the Plen-an-Gwari (Place of the Play) in the heart of the town. This is one of only two surviving Cornish medieval amphitheatres that were once used to perform miracle plays in the Cornish language.

Not all the Bards are Cornish. Some come from as far away as Australia to be conferred. Just before the ceremony I chatted to the circle steward, who has taken the name Karer an Yeth (Lover of the Language). He is a Londoner who works for British Airways and became a Bard by chance. While holidaying in Cornwall, curious about the Cornish place names on every signpost, he sent away for information. A free lesson in Cornish came back in the mail. After the first lesson he was hooked and he eventually became a fluent speaker and teacher. There is renewed interest in it, he said, and his London classes fill quickly. To become a Bard, he told me, there is a rigorous examination and it is then necessary to outline a plan for passing on one’s learning to others. Many of the Bardic names signify the vocation or the special interest of the bearer: Spinner of Tales, Celtic Dancer, Musical Wanderer, Guardian of the Heritage, Lover of Plants.

The woman pictured wearing the crown and blue robe with gold edging is the former Grand Bard, Elizabeth Carne. She spoke eloquently in a mixture of Cornish and English of the need to preserve friendship and inclusiveness among Cornish people as they celebrate their unique cultural identity.

When I returned home, my friend was amazed that I’d stumbled on the ceremony just as it was starting, completely by chance. ‘When was the last time it was held at St Just?’, he asked. I looked it up – the last time was fifty-five years ago.

Weblinks

St Just on the remote tin coast has a long and proud cultural heritage and its plen-an-gwari (place of the plays) has a central role, as explained in this short film.

The Cornish Language Fellowship produces a wide range of Cornish language publications and offers online Cornish conversation groups.

Explore Akademi Kernewek’s Directory of Cornish Place Names.

Sources

Collett, Richard, Why Cornwall is Resurrecting its Indigenous Language, BBC.com, 24 April, 2023

Marsden, Philip. Cornish Identity: why Cornwall has Always been a Separate Place, The Guardian, 26 April, 2014

Pool, P.A.S. The Death of Cornish, pamphlet from an address to the International Congress of Celtic Studies, Penzance, 1975.

Waken, Martyn Francis. Language and History of Cornwall, Leicester University Press, 1975